Did Medieval Nations Exist?

During the medieval Holy Roman Empire (HRE), there were a multitude of regions that were ruled by a host of different rulers. But to whom did they owe their allegiance?

What is a Nation?

In the modern world, we often think of a nation as being both culturally and politically distinct from its neighbors formed by a collective identity of shared kinships, customs, and beliefs. In German, this is sometimes referred to as a Kulturnation—or cultural nation.

Typically, the closer the neighbor, the more similar they are, like Germany and Austria. On the other hand, Germany and Poland are both very distinct linguistically, culturally, and politically, yet far more similar to one another than either is to a country like Turkey, for example.

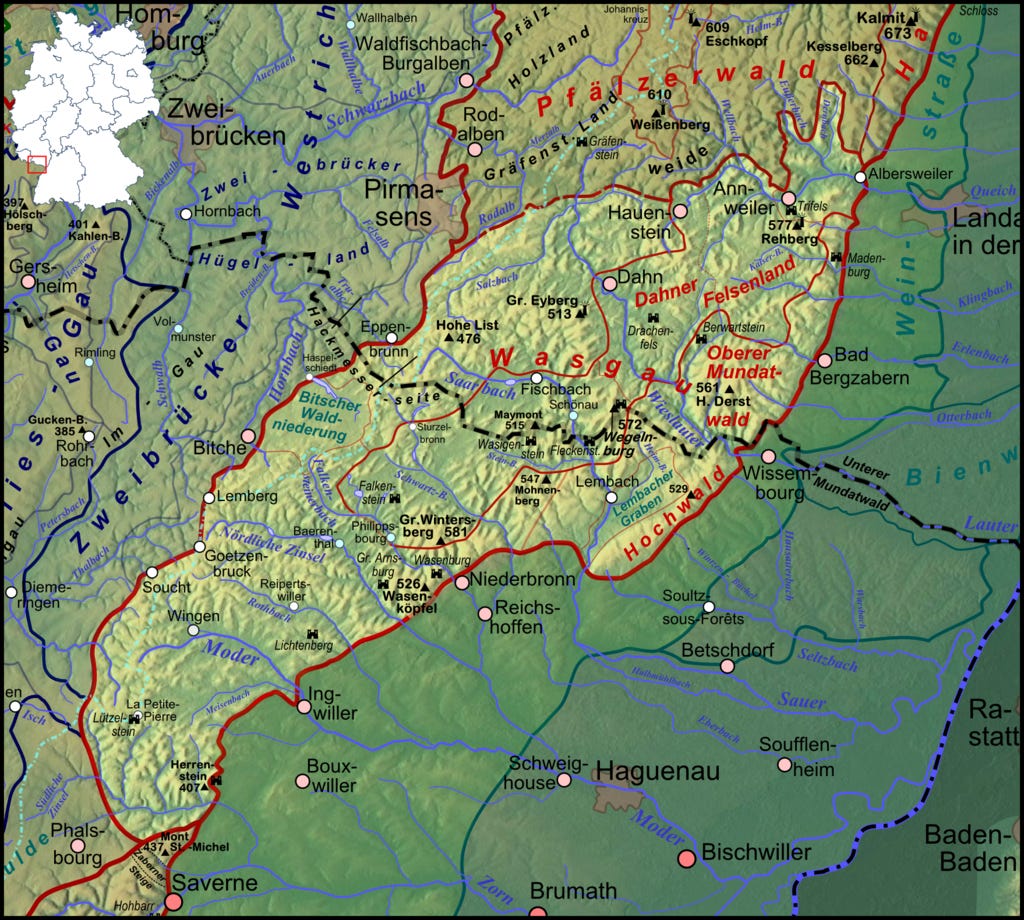

The modern political borders do not necessarily denote a hard cultural distinction. For example, take the border between France and Germany. The people of on either side can understand each other’s dialects—though admittedly at times with some difficulty—and the regional architecture is nearly identical. Even the natural landscapes are the same—the Vosges of France moves seamlessly northward into the Wasgau of Germany despite the political border that cuts through the middle.

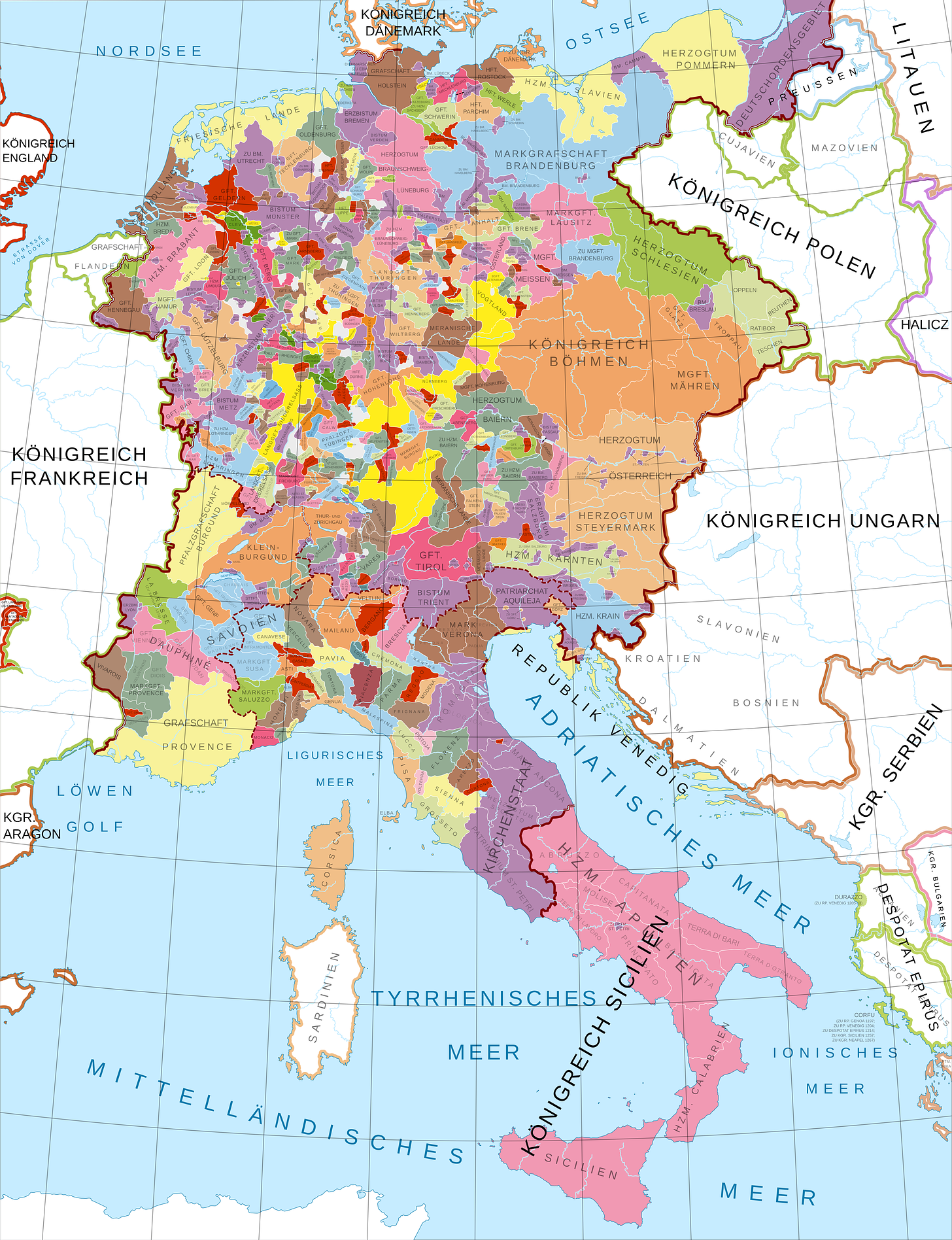

The phenomenon of shared cultures, whose only separation is a relatively unenforced political border is not new to Europe. Medieval states, like the Electorate of the Rhine, or early modern states like the Kingdom of Prussia included numerous lands that were not even connected to the bulk of the territory, but still belonged to the same state.

What is the Basis of a Shared Identity?

The sometimes odd shapes of medieval states were due to a number of factors, including kinship bonds among the nobles, but most importantly—for the discussion of the Middle Ages—it was due to enfoeffments by the kings and emperors. Enfoeffments were essentially territories or objects belonging to a prince that were loaned to a servant or loyalist to maintain in their stead. Considering the size of some territories and the limited avenues of communication, it was far easier to entrust lands to a servant or friend than to struggle to maintain it oneself.

This created networks of trustees of the enfeoffing prince who were allied to one another so long as they served the same interests. The moment a certain enfeoffment changed hands, the former holder no longer had any political association with his former fellow-trustees—assuming, of course, it was the only thing enfeoffed. To prevent factions from forming too quickly, multiple princes would sometimes enfeoff the same person with different lands.

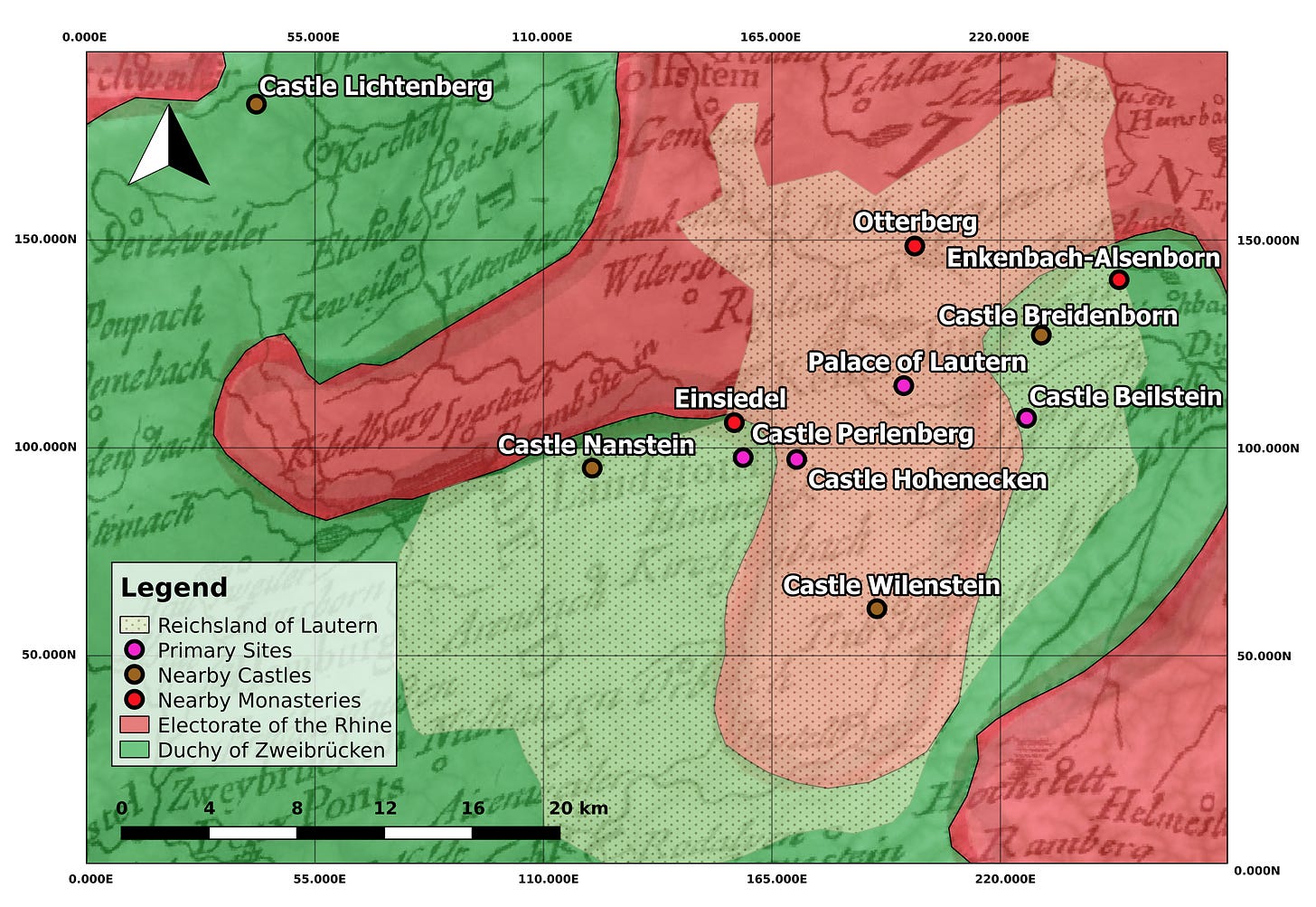

Take for example Castle Hohenecken, in city of Kaiserslautern, Germany. The site was commissioned in the late 12th century by the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick I, built by the family of one his most trusted ministeriales (the von Lautern-Hoheneck family), and then given as an enfeoffment to that family along with a number of villages and lands rights through the imperial territory of Lautern.

During the Interregnum from 1245 – 1273 AD (the period without an uncontested king), the von Lautern-Hoheneck family began selling lands and rights that had been given to them as enfoeffments to other ministeriales, nobles, and monasteries. When Rudolf of Habsburg was elected Roman-German King in 1273 AD, he removed the remaining enfoeffments from the family and handed them to the von Leiningen family—a noble family and loyalist of the king who doubled as the main regional opponent of the von Lautern-Hoheneck family.

The formerly enfeoffed von Lautern-Hoheneck family at Castle Hohenecken was allowed to remain in the castle, but were now subservient to the Leiningen family. Despite all of this, the family kept the revenue gained from selling rights that had originally been enfeoffed to them. This then raises the question: who owns the land?

The land was still part of the imperial territory, the revenues flowed into the coffers of the von Lautern-Hoheneck family as well as the noble Leiningen family, who in turn paid taxes in the form of goods or coin to the king. Thus, despite the political gymnastics, the king still received what he was owed and the land was maintained.

However, something happened in the process: a complex network of interactions occurred binding different parties to one another in the form of economic partnerships, marriages, friendships, and even enemies. Over time, these bonds grow deeper, drawing the people within that network closer together thereby forming a culture of shared identities, kinships, and customs.

Furthermore, these regions contained many different, smaller cultural realms that could be differentiated from one another based upon locally shared identities. Take, for example, the region of the German Palatinate and Nahegau, nestled along the southwestern side of the middle-bend of the Rhine River. During the High Middle Ages, this region was home to: the County of Veldenz, the County of Leiningen, the County of Sponheim, the Electorate of the Rhine, the Archbishopric of Mainz, the Bishopric of Speyer, the Bishopric of Worms, and the massive imperial estate located around the Palace of Lautern.

Despite these various lords, whose dynasties came and went, the people of that region shared a common identity. The rule of law even experienced changes with the shift in leaders, yet the identity of the people forged in the High Middle Ages did not change much. They still celebrated the same festivals and spoke the same dialect. How could that be?

The involvement of the bishoprics in various realms through the prebendaries, the rise of the ministeriales, and the legal structure of the Church that transcended all borders essentially prevented large political entities from taking complete control, thereby changing the predominate culture. Thus, the identity that the people shared within a particular state, like the Electorate of the Rhine, was their specific faith, not their fealty to the Prince Elector.

After the Prince-Electors of the Rhine converted to Calvinism in the mid-16th century, they forced their people to convert as well. Resistance to that rule arose periodically, much like in England after the formation of the Church of England. The change in religion forced a change in culture.

When did Nations Come About?

The rise of nations—within the context of the HRE—is a product of the 17th century in which the prince-electors slowly separated themselves from the suzerainty of the emperor and of the Catholic Church during the incredibly bloody 30 Years War (1618 - 1648 AD). However, the movement really began roughly a century beforehand during the Protestant Reformation, in which states like the Electorate of Saxony seized the opportunity to revolt against the HRE brought about by Martin Luther’s discord. Although Luther may have only wanted a religious debate and reformation, his patrons and the secular princes who enabled him wanted something very different.

By initiating a religious separation, the princes forced a decision upon their subjects: fealty to the prince and his new religion or fealty to the Catholic Church. Given the manifold local cultural groups, not all who remained within a separatist state actually regarded their prince’s religion as the object of their unity—which in turn caused migrations to and from Protestant states.

The removal of the Catholic ecclesiastical system in new protestant states prevented regular outside oversight and the taming of political aspirations, allowing these princes to rule with unprecedented might. After all, revolutions, both political and religious, sever connections with the past thereby forcing a new turn in cultural norms.

These early national formations found their completion in the first half of the 18th century where newly formed kingdoms (e.g. Prussia) initiated social and political reforms that were not only separate from the Catholic Church, but also state-specific.

These included the creation of the Beamten (civil servants) and endowment of universities to support the secular Prussian cultural goals, most notably in Göttingen and Halle. In turn, the other new kingdoms acted in like manner, each developing along a slightly different trajectory.

However, in the medieval HRE, secular leaders lacked the legal independence to issue lasting reforms specific to a territory under their control. All reforms and legalities had to be checked and approved by the Church, thereby ensuring a consistency that was difficult to dent by ambitious princes.

Case in point: the Hohenstaufen Emperors Frederick I, Henry VI, and Frederick II (the three ruled as emperors between 1156 and 1245 AD) routinely attempted to establish a empire in which elections of kings would cease to exist and where their own supporters would gain the reins of power. However, upon the death of each emperor—or the fourth excommunication in Frederick II’s case—these plans unraveled and everything returned back to the structure of royal elections, ecclesiastical checks and balances, and local allegiances to liege lords.

Despite their ability to gain monumental support in waging war campaigns, building thousands of castles and churches, and making treaties with Muslims and Christians alike, the structure simply did not support their designs for a unified state—the medieval HRE was inextricably bound to the Church and its oversight. Thus, the idea of the HRE as a nation, or even as a Kulturnation—as indicated in the 15th century title of the HRE as Heiliges Römisches Reich deutscher Nation (Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation)—could only apply within the context of an unsevered bond between the Catholic Church and the empire.

For more reading on nations and the development of the HRE:

Bergman, Rolf. “Deutsche Sprache und Römisches Reich im Mittelalter.” In Heilig Römisch Deutsch: Das Reich im mittelalterlichen Europa: Internationale Tagung zur 29. Ausstellung des Europarates und Landesausstellung Sachen-Anhalt “Heiliges Römisches Reich deutscher Nation 962-1806 - Von Otto dem Grossen bis zum Ausgang des Mittelalters,” edited by Bernd Schneidmüller and Stefan Weinfurter. Ausstellung des Europarates und Landesausstellung Sachen-Anhalt 29. Dresden: Michael Sandstein Verlag, 2006.

Bosl, Karl. Die Reichsministerialität Der Salier Und Staufer: Ein Beitrag Zur Geschichte Des Hochmittelalterlichen Deutschen Volkes, Staates Und Reiches. 1st ed. Vol. 1. Schriften Der Monumenta Germaniae Historica (Deutsches Institut Für Erforschung Des Mittelalters) 10. Stuttgart: Hiersemann Verlag GmbH, 1950.

Engels, Odilo. Die Staufer. 8th ed. Geschichte/Kulturgeschichte/Politik 154. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer GmbH, 2005.

Hagen, Joshua. “Rebuilding the Middle Ages after the Second World War: The Cultural Politics of Reconstruction in Rothenburg Ob Der Tauber, Germany.” Journal of Historical Geography 31, no. 1 (January 2005): 94–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2004.04.002.