Does Text Change our Perception of Time?

The invention of the printing press shifted Western Civilization from an image culture to a text culture. What did we gain and what did we lose in that process?

The topic of ‘time’ in the Middle Ages has garnered a fair amount of interest lately, especially if you have been reading Robert Keim’s phenomenal substack, Via Mediaevalis (and if you have not, then you certainly should!). His explorations into the understanding and perception of time in the Middle Ages is nothing short of fascinating, laden with medieval images and illuminations in triumphant support.

Realism in the Middle Ages?

Medieval artists often discarded materially limited aspects of time, such as the change in clothing, armor, and architecture. An adherence to portraying historically accurate materials developed over the course of the 17th to 19th centuries, reaching its zenith in the Age of Realism.

However, the public’s taste for art quickly shifted towards styles that did not observe a strict obedience to realistic qualities—after all, the photograph was achieving just that. This speaks to the the desire of people to see more than what lies visibly before them—a desire to look beyond the the limitations of space and materials. What can painting or sculpture accomplish that a photograph cannot?

Unlike the artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries who created new techniques, experimented with a new medium, or sought to paint a specific emotion, the artistic experiments of medieval artists were aimed toward one goal—to illustrate the complete picture. The stylistic abstractions or experiments in media were secondary.

Furthermore, medieval artists painted or sculptured historical figures and events in the clothing and settings of their own time. The effect of this stylistic choice brought medieval contemporaries into closer contact with historical figures and events, effectively stripping the chronological barrier that separated a medieval French peasant from King Solomon, for example.

During the Renaissance of the 16th century, this habit—or rather stylistic choice—slowly died off. Although artists like Albrecht Dürer or Lukas Cranach the Elder continued to depict historical figures in the fashion of the 16th century, later artists did not. Why did the change occur specifically at that time?

The Image Culture

The medieval world was highly visual, placing an immense importance on images, architecture, and sculpture as the key modes of non-oral communication. In contrast, the literary world of text was fairly restricted to those with a classical education and libraries were typically only found in monasteries, cathedral chapters, or extremely wealthy lords until the end of the 15th century.

In contrast, access to paintings, architecture, and sculpture was mostly unrestricted. The great medieval churches were always adorned with the most exquisite ornamentation that the patrons could afford, ranging from architectural tracery, to entire biblical scenes carved within the tympanums above portals or as sprawling reliefs stretching across the facade.

The churches themselves were often the main meeting points in every town, operating not only as centers of worship, but as centers of learning. The ringing of the bells indicated the hours of the day and the eastward orientation of the high altars indicated the cardinal directions within cities where it was easy to get turned around. Most importantly, the frescoes and sculpture within the churches proclaimed the Gospel to the laity.

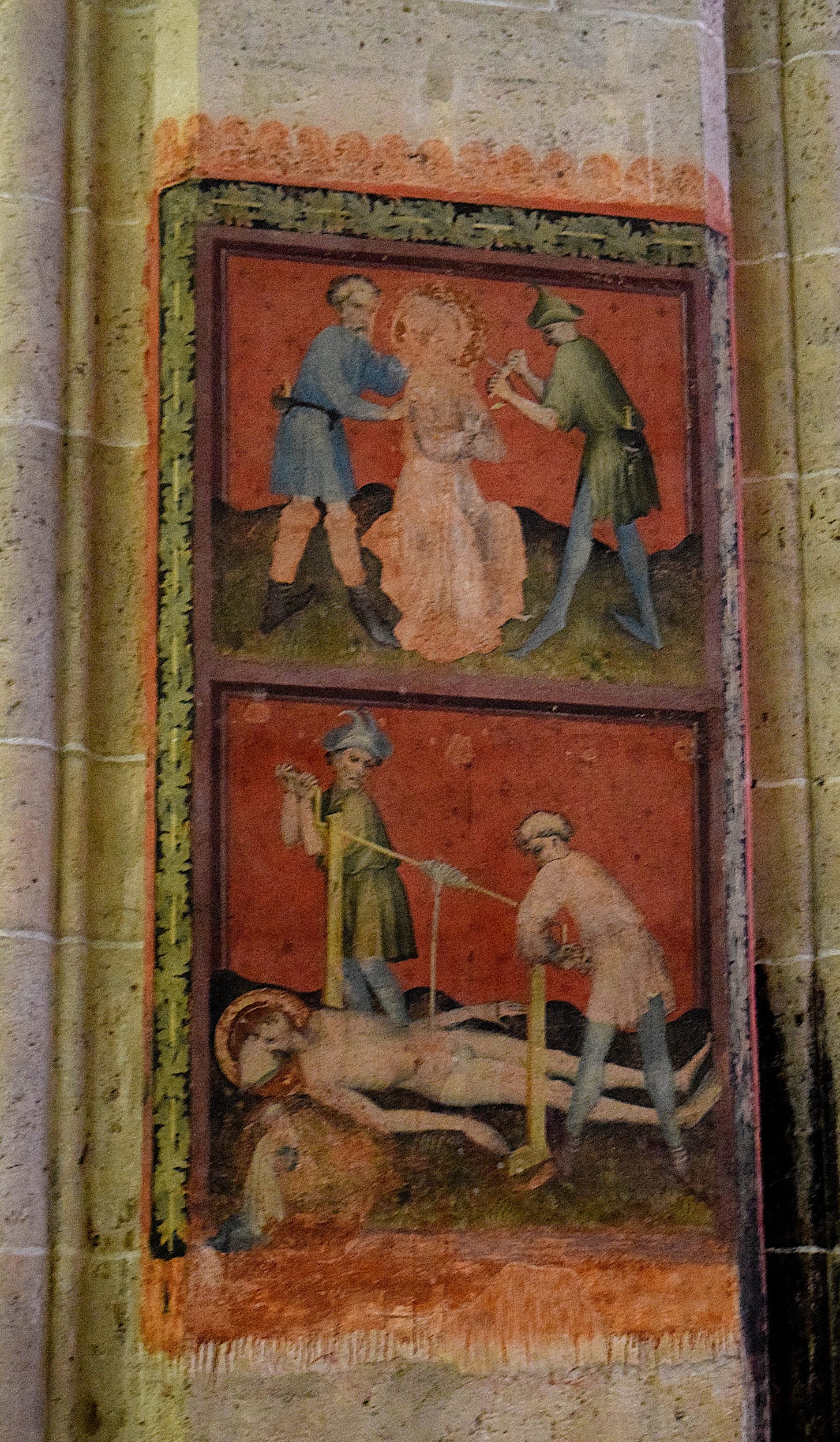

Christian education of the common folk was performed through artwork. The stories of the Old and New Testaments painted on the walls and the symbols of the saints provided visuals of the stories for the medieval folk. And, as previously mentioned, these images were produced in manner matching the daily life of medieval people. The Roman persecutors of Christ were not depicted in 1st century Roman armor, but in armor that was modern at the time of the painting’s production.

This provided people with a closer, more colorful, and more intimate connection to Christ and his sufferings—for he suffered at the hands of those who looked like them. The weapons causing the martyrdom of the saints were depicted as weapons medieval people used, rather than those of antiquity. Even pharaohs looked like medieval kings wearing golden crowns, rather than the uraeus.

The Beginning of Mass Literacy

The 15th century introduced a number of startling changes into the daily lives of medieval folk, but none had such a lasting effect upon how people viewed their world than the printing press. The design that changed everything was the combination of a wine press with type set, built by Johannes Gutenberg in the city of Mainz in the 1440s AD. He accomplished this feat under the jurisdiction of the Archbishop and Prince Elector of Mainz, and his new press revolutionized communication via text by speeding up the transcription process.

By the turn of the 16th century, it was no longer necessary to have large scriptoria in the monasteries filled with monks meticulously transcribing texts from parchment to parchment and painting magnificent illuminations on the pages. Now, a text could simply be written by the author, the type set by the pressers, and the printed page distributed within a single day.

The invention of this press caused both a material and immaterial shift in the transfer of knowledge. The increase of text meant a greater reliance upon literacy, and the convenience of the press, meant less patience for art as a mode of communication. Instead, artwork began to accompany text, and not the other way around.

One of the first examples of a book printed on a press, the Schedelsche Weltchronik, was published in 1493 AD by Anton Kroberger in the city of Nuremberg. Its text-laden pages were supported by regular intervals of prints of wooden etchings carved by artists, such as Albrecht Dürer, and quickly set the standard for future educational texts.

Ideally, the spread of text meant the spread of knowledge and the spread of the Gospel—as was the intention of the Archbishop’s support for the new printing press. Unfortunately, the speed at which text could be produced limited the time required to proofread political and theological works. One of the main reasons as to why the proposed reformations by Martin Luther (†1546 AD) spread so quickly and those by Jan Hus (†1415 AD) did not.

The increase in access to knowledge caused a desire for more knowledge. Previously, written works were the product of time-intensive proofreading before the monks of the scriptoria even began their transcriptions. The transcriptions themselves were made on stretched leather parchment (or vellum), for which one sheep provided an average of only four sheets—thus, eight pages of text (a future article will cover this process in more detail).

The completion of the transcriptions did not mean the end of the book, as the heading and spaces reserved for illustrations had to be finalized and the page bound by hand. Printed books also needed to be bound, which is why most authors eager to transmit their ideas printed small brochures whose pages could be quickly sown together and distributed.

The Text Culture

The revolution in the transmission of knowledge by the printing press introduced a sense of urgency by many authors to not only write but to be heard. However, quickly produced ideas do not immediately translate as good ideas. Likewise, printing half-baked ideas does not provide an actual, Aristotelian good for the consumer of those ideas.

The time required for producing artwork and transcribing texts by hand guaranteed the authenticity of artist’s or author’s intentions, not necessarily the good of their ideas. However, the rapidity of the printing press guaranteed neither. The sense of time changed with the press—and especially during the rise of Protestantism—as time was now of the essence to spread ideas, respond to dissenters, or to encourage allies.

Previously, theological debates were performed in-person, with months taken in between each meeting in order to ensure the quality of the argument. In contrast, the printing press’ ability to produce brochures eliminated the necessity of meeting in person, though this had considerable drawbacks.

Take, for example, the flurry of correspondences by the 16th century Protestant leaders—whether by hand-written letter or printed brochure—whose impatience clearly indicate that most were speaking past one another and likely had, in their haste, not properly considered the arguments of their opponents.

This frantic search for knowledge and discussion, led to a depletion not only in the quality of their arguments, but also in authenticity of their search for truth—much in the same way that individuals use the internet. It also correlated with a tremendous shift in how art was being used.

The effect of the printing press on artwork was a gradual shift from the necessity of art as a main mode of communication, to consuming art as demonstration of status among the elite. If the Catholics and Lutherans had not continued the commission of sacred artwork to adorn the interiors of their churches available to the public, then art would have drifted entirely into a luxurious, leisurely pastime for the elite.

The Linearity of Text

Text replaced art as the modus operandi of communicating the Gospel and ideas. To its credit, text has allowed far more people to interact with ideas, educate themselves, and be a part of philosophical, medical, legal, and theological discussions. However, it does so only linearly. A text narrative follows from beginning to end, i.e. from A to Z. There may be slight diversions along the way, but the general direction is always the same.

Communicating in this mode simplifies things and allows people to follow the narrative more easily, this is part of the reason for the success of the doctrine of Sola Scriptura followed by some Protestants. However, by simplifying the overall message, intrinsic complexities must necessarily be omitted. If one follows a strictly linear thought process—i.e. a text—how would it be possible to explain Mary, the Mother of Jesus, as queen of heaven and angels in brief? Did she come before or after the angels? Did the fallen angels know about her before her birth and, if they did, then how?

Text cannot answer these questions in a simple manner, thereby requiring almost arcane literary skills to transmit the Catholic understanding of her soteriological role when given only a short timeframe to do so. However, a painting can tell many parts of a story without relying upon a linear timeline. Whereas complicated texts require a formidable scholar to unpack the various meanings, artwork triumphs in illustrating the interconnectivity of people and events and even allows onlookers to do so at their pace.

Thus, statement of ‘a picture can say a thousand words’ is nearly correct. It ought to be ‘a picture can say a thousand ideas.’ Medieval artwork tells many stories all at once, and even illicit certain emotions that open one’s mind to understanding the complexity of what the artist is trying to show.

Artwork provides a personal connection that changes over time as one learns more about the symbols, requiring solitude, study, and reflection. Text also requires these attributes, but in a world replete with narratives, stories, and commentaries who has the time?

One thing that should be added which complicates but reinforces your main point: Mary Carruthers in The Book of Memory shows convincingly that medieval approaches to text were highly memorial (because books are scarcer, you as reader have to commit more to memory), and that practically this means making use of mental images among other techniques to memorize text. So on the one hand it’s not that the elite are only textual, but that their way of being textual is highly bound to the image.

Bravo! The importance of art for the understanding of theology cannot be overstated.