Medieval Servants were Basically Slaves, Right?

There is a commonly-held belief that medieval servants were slave-like serfs subject to every desire of the nobles, being fed scraps and sent to their quarters like livestock at dusk. Is that true?

An Ongoing Injustice

The false portrayal of medieval social structures and rights depicted by filmmakers and novelists is only matched by the perjury of those who know better. Academic scholarship has often made an unfortunate habit of omitting legal history from discussions of politics, society, and economics. As an academic, I hold myself accountable to this grave error and to the same standard as much as anyone else.

It must be said, perhaps to the disbelief of some readers, that the number of scholars who willingly misconstrue the facts to fit their narrative is relatively small. It is more often the case that academics will omit portions of the broader canvas deemed out of scope in order to remain focused on their topic at hand—however myopic it may be at times. After all, historical investigation always begins by casting a wide net and then looking for the specific fish, so-to-speak, that matches the appetite of the inquiry.

It is for that reason that so many of the other fish—to unabashedly extend the metaphor—get thrown back into the vast seas of the unknown. The documentation of the Middle Ages has been well-curated, but that does not mean every document has been well-studied. Nor does it mean that every well-studied document has been fully integrated into the general knowledge of historical education. Nevertheless, the information exists, but requires the due diligence of finding it.

With the exception of a multi-disciplinary and large research group, historical inquiries seeking to weave legal and social histories with regard to rights, privileges, and inequalities into an all-encompassing study is nearly impossible. The only alternative is to take bite-size portions at a time in the hope of consistently identifying the commonality between each portion.

As this aligns with the goal of Maintaining the Realm, as today’s offering will discuss the main legal documents of the High Middle Ages that outlined the rights, privileges, and inequalities of the ministeriales of the Holy Roman Empire (HRE) who accounted for roughly 30% of the population. The review of their position in society and the connotations associated with their status has been discussed in a previous article, allowing us to jump right in.

Dienstmannschaftrecht

Bear in mind that the status of ministeriales was unique to the HRE during the Middle Ages. In fact the HRE was unique in more ways than one with regard to legal protections for unfree people. Three key documents were issued within a 50-year span during the 11th century outlining the specific obligations, rights, and privileges of the ministeriales serving in episcopal, royal, or imperial courts.

1025: Lex familiae Wormatiensis ecclesiae (Law of the familiae of the Bishopric of Worms)

1057: Dienstmannschaftrecht of the Bishopric of Bamberg

1070: Dienstmannschaftrecht of the royal court of Weissenburg

The first hurdle is to explain what the word Dienstmannschaftrecht means. German often makes extraordinary use of compound words that need not be formally defined in dictionaries. Instead, the language allows for its speakers to combine words in order to communicate an idea, otherwise necessitating a sentence or two, while remaining entirely lucid to German-speakers what is meant by the word.

To that end, we shall break the word into its components:

Dienst: service, commission, or ministry.

Mannschaft: team, crew, or squad.

Recht: rights, law, or privilege.

To summarize: the rights and privileges of the team of servants commissioned in a certain ministry. Within the context of the 11th century, this team of individuals were collectively known as the familiae, Latin for household often considered as a single unit, or in German, a Dienstmannschaft.

Within the familiae were people belonging to different non-noble status groups inextricably bound to their commissions, while retaining a strict hierarchy among themselves—not mention with regard to the nobles. Thus, the daughter of a ministerialis commissioned as a marshal was of a higher status than the son of a ministerialis commissioned as a bailiff, for example.

Women also held commissions within the households in a variety of capacities ranging from chamber maid, to beer-brewer, to assistant of the ladies-in-waiting. In fact, it would be remiss to omit that the vicinity that some women had to the noble ladies translated to a more elite network for their respective families, quite pertinent for marriage strategies.

Precedence Set by the Lex familiae Wormatiensis ecclesiae

According to Paragraph 29 of the Lex familiae Wormatiensis ecclesiae issued by Bishop Burchard, a description of the duties of ministeriales was given, based upon the tradition of the king’s men, known in the text as fiscalini. They belonged to a higher status of unfree people and were not allowed to take servitium (servitude) other than that of camerarius (chamberlain), pincera (cupbearer), infertor (dapifer, seneschal, or steward), or agaso (marshal).[1] These four elite positions would continue as the definitive ministeriales positions well into the 13th century.

The position of agaso, or marshal, is the most notable within the historical charters beginning with the ministeriales of Emperor Otto II (955 – 983 AD)—who at that time were referred to more generally as servientes in the charters. By that time, they already composed a large portion of the loricati (armored infantry) partaking in Otto’s Calabrian campaign in the late 10th century.[2]

This trend continued, as ministeriales were filling the ranks of Emperor Henry III’s (1016 – 1056 AD) personal army and were distinguishing themselves as warriors, according to the Annals of Altaich.[3] For their services, Emperor Henry III recommissioned his ministeriales in the regions of the royal estate after the campaign, specifically in the imperial territories, along the Rhine and west of the Rhine. They were given forestry rights and were responsible for the administration of the various royal palaces, such as those in Nijmegen and Kaiserswerth.[4]

According to the Lex familiae Wormatiensis ecclesiae, a ministerialis not commissioned with a task by the king was allowed to serve another lord, as was also the case for the Dienstmannschaftrecht of the palace of Weissenburg outlined 45 years later.[5] This meant that ministeriales had the right to pursue employment elsewhere if they had no commission, and did not need the approval of their lord to do so.

The ministeriales in these higher positions were also compensated if they were to be removed from service—quite contrary to the notion that all servants were simply fired and left out in the cold. For example, Saint Emperor Henry II of the Ottonian dynasty, included a compensation of 10 Pounds Silver for the ministeriales his dismissed who had been involved in a struggle between the ecclesiastical foundations of Worms and Lorsch in 1023 AD, which had led to multiple deaths.[6]

The Mid-11th Century Developments

The ecclesiastical Dienstmannschaftrecht of the Bishopric of Bamberg from the years 1057 to 1064 AD, and the secular Dienstmannschaftrecht of the royal court of Weissenburg (in modern-day France near the German border) from the years 1070 to 1080 AD, marked a decisive progression regarding the status of the ministeriales.

The latter included rights for all members of a ministerialis’ family including the sons, who were allowed to serve another lord when not commissioned by the king, and for daughters who were never to be forced into becoming a lady’s maid. However, in the event of campaign to Rome, or on the eve of any military excursion, the daughters were to sow and mend the garments of the warriors—presumably those of their own family members and of others serving the royal household.[7]

The ministeriales were also given hunting rights, fishing rights, and hay production rights of the royal court in Weissenburg in the imperial forest.[8] The duty of the ministeriales to serve as foresters was also a component in the Bishopric of Bamberg, in addition to the positions of chamberlain, butler, marshal, and steward.[9]

Their military service to the emperor was also compensated: each ministerialis accompanying the emperor on an Italian campaign was given 10 Talents (typically of silver), the shoeing of five horses, two goat hides, one mule, two additional mules carrying weapons and armor, and two servants each with one horse and a wage of one Talent. However, the monetary payment was only to be given once the emperor had crossed the Alps.[10] In the event of an expedition into other lands—i.e. north of the Alps—each ministerialis was to be paid five Talents, given one burden-less horse, the shoeing of five horses, and two goat hides.

The amounts dictated by the secular Weissenburg Dienstmannschaftrecht were substantially larger than those granted by the Bishop of Bamberg, and were perhaps the reason as to why Conrad II’s imperial successors continually sought to gain control of the wealthy Italian cities and the various silver mines near Goslar in order to pay the wages due to the ministeriales.[11]

The ecclesiastical Dienstmannschaftrecht of Bamberg also addressed military excursions, describing the wage of a ministerialis to include one horse and three Pounds (typically of silver) for each Italian campaign[12]—a considerably smaller amount than what was granted by the emperor. Additionally, in the event of a campaign north of the Alps, the ministeriales were expected to pay their own preparatory costs and await a subsidy from the bishop at a later point.[13]

However, the Dienstmannschaftrecht of Bamberg clearly indicated the hereditary legacy of the ministeriales and their knightly character,[14] fulfilling one requirement identified by the scholar Werner Hechberger regarding the heritage of a noble,[15] in stark contrast to the Dienstmannschaftrecht of Weissenburg, which did not include this aspect at all.

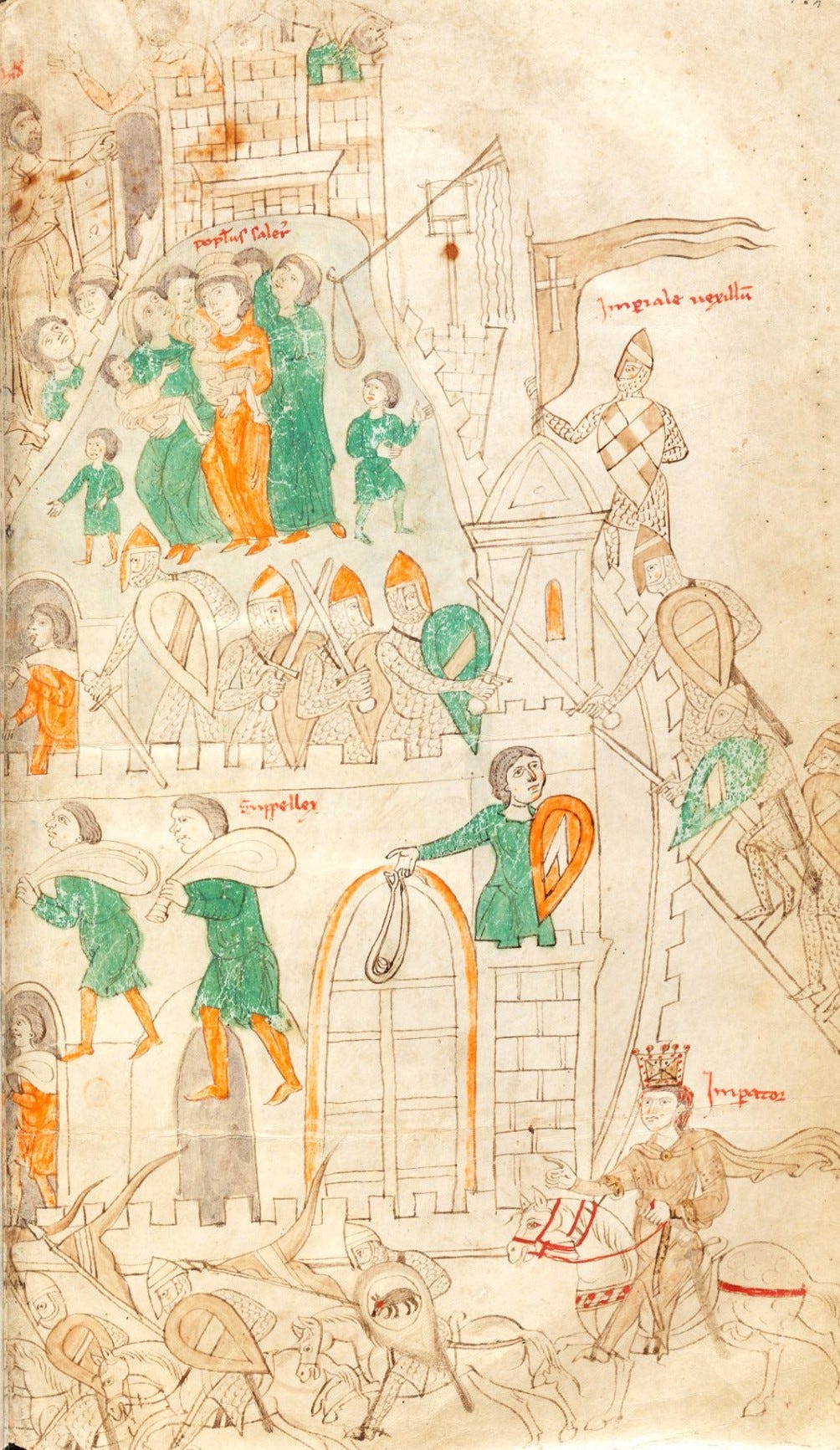

The rights of the ministeriales issued by the Bishop of Bamberg coincided with the reign of Emperor Henry IV (1050 – 1106 AD) who was famously humbled at Canossa in January of 1077 AD in which he begged Pope Gregory VII to rescind his excommunication as part of the ongoing Investiture Controversy briefly discussed here.

It was during this time that the ministeriales loyal to the emperor—known in the charters at that time as minister regis—were commissioned to execute a territorial policy of the empire that ran parallel to the policy conducted by the bishops and nobles.[16] This policy also included the reconstruction of destroyed castles from the year 1076 AD, which stood in the various imperial territories of the empire. In essence, the scandalized emperor used his ministeriales to continue enforcing his policies when the princes of the empire refused to support him, indicating that they were of such significance that they could actually blockade the nobility.

The construction and expansion of castles in the various imperial territories introduced the position of Burgmann (castellan) occupied by a ministerialis—thus adding to the list of elite positions that could occupy. Furthermore, a deeper study into the genealogies determined that many of these ministeriales commissioned as castellans had at least one parent who belonged to the nobility,[17] presumably to bridge the ever-widening gap between the nobility and the ministeriales, and to bring about some sort of consensus between the two groups.

The conflict between Henry IV and the nobles resulted in the increase of ministeriales as administrators in the courts and the general implementation of his expansion policy. This led many nobles to renounce the royal ministrī through open statements of disdain, particularly against the Swabian ministeriales placed in Saxony during the Saxon-uprising of 1073 AD.[18]

In the following decades until 1100 AD, various bishoprics began granting their ministeriales additional rights. Of particular relevance was the right of free marriage granted by Bishop Udo of Hildesheim to all of his servientes legitimi (lawful ministeriales), in-line with the same right granted to the servientes regnum pertinentes (the most splendid royal ministeriales) of the king, and those serving in the Archbishopric of Mainz.[19]

Marriage Policies

Marriage strategies among the ministeriales of all three levels (see previous article for their description) essentially followed a pattern that correlated with the family attaining a higher status either within the familiae of their commission, a different familiae, or into the nobility.

When men of either the nobles or the familiae married, their wives were generally from a status above them. For example, an imperial ministeriales wishing to move his family into the nobility had essentially one opportunity to do so: to marry the daughter of a count.

Even the famous ministeriales like Markward von Annweiler († 1202 AD) and Eberhard von Lautern († ~1240 AD) who each ruled vast swaths of Italy, commanded entire armies, and advised emperors, never achieved nobility through their actions. Others who achieved far less, like Eberhard’s kinsman, Reinhard III von Lautern, who managed to marry the right woman, secured a far brighter future for their families.

This hurdle was even higher for the ministeriales of a lower status to effectively ‘jump over’ the status above them. For these lower ranking ministerialis groups—i.e. those serving bishops, counts, or monasteries—marriage was restricted to within their status group, while allowing meritorious men from the lower common-folk status to marry into their families.

In the event of a marriage and subsequent birth of children from parents belonging to two different status groups, the question arose as to whom the child would be raised to serve? The legal solution was known as maternal ascription, citing the Roman legal maxim that the offspring follows the womb (partus sequitur ventrem).[20]

Still other nobles determined that the children of the ministeriales serving them ought to receive the legal status of the inferior status, regardless of the mother—who was often times the higher status. This was essentially a discrimination of the ministeriales as part of an agenda to prevent them from eventually marrying into the nobility—a policy that was largely influenced by the struggle between the nobles and ministeriales during the reign of Emperor Henry IV mentioned earlier.

This marriage practice in which a man of lower status courted a woman of higher status applied to the nobles as well. Counts married the daughters of margraves or landgraves, whose sons married the daughters of dukes. The system continued upward until one reached the imperial houses, at which point it was necessary to marry a woman of equal status—i.e. marry a Byzantine princess, or princess of an illustrious royal house.

As the tether between not only families, but gradations in status, the women had to learn how to operate in both cultures. Although the men were expected to prove themselves to the woman’s family as worthy of her hand and likely had much contact with his in-laws, the woman herself was expected to move into the home of her husband’s family—even in the context of a nobleman’s household—which meant moving from a more elite dwelling to a slightly lesser one. This shift brought with it many challenges consisting of differences in manners and etiquette, cultural customs, and sometimes strained relationships with in-laws.

The practice of families attempting to enter into a more elite group via marriage is well documented for the medieval HRE. However, these findings are largely based upon marriage strategies between the years 1400 and 1699—the late Middle Ages and Early Modern Period. Still, plenty of evidence points towards a German phenomenon of men of lower status groups marrying the daughters of men of slightly higher status groups in an attempt to enter that group.[21]

Within the time frame from 1200 until 1550, the marriage rates among the daughters of counts and barons was much higher than of other cohorts belonging to the group of imperial princes—65% of daughters and only 55% of sons married at all.[22] This is an indication that the pool of suitors was much larger for the daughters who married downward, as opposed to the sons, who were expected to marry upward. Within the context of the ministeriales, this demonstrates that the higher status ministeriales were courting the daughters of counts and barons.

Additionally, both nobles and ministeriales sought to place sons within the ecclesiastical structure. Many ministeriales even became bishops, such as Landolf von Lautern-Hoheneck, who was elected Bishop of Worms in 1234 AD.[23] Daughters also became sisters and abbesses, serving alongside figures such as St. Hildegard von Bingen.

Summary

Those belonging to the household (or familiae, or Diensmannschaft) of the nobles learned to act as the nobles. It was a grand imitation game that eventually muddied the waters between the two to such an extent, that a differentiation was hardly recognizable by the early 14th century. This, of course, only applied to those families within the household clever enough to align each member with the strategy of striving for a higher status.

The nobles also required the ministeriales of the households to succeed in this manner to replenish the pool of suitors in order to maintain genealogies free of too much intermarriage. The HRE served as the key center of Europe not only economically, but also with regard to marriage policies as it clearly had a structure allowing its gene-pool to be consistently and constantly resupplied well into the modern period (e.g. the family of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha).

These members of the households were given the right to choose whom they served, except for the ability to not serve at all. Their commissions were defined, their compensations were clearly outlined, and their merits were duly rewarded.

Some sections of this article were adapted from my dissertation entitled CITADEL—Computational Investigation of the Topographical and Architectural Designs in an Evolving Landscape, available here.

[1] Bosl, Die Reichsministerialität Der Salier Und Staufer: Ein Beitrag Zur Geschichte Des Hochmittelalterlichen Deutschen Volkes, Staates Und Reiches. Pp. 38-39. The term fiscalini calls to memory the description of the fiscales regni from the Chronicon Ebersheimense mentioned earlier.

[2] Arnold, “German Bishops and Their Military Retinues in the Medieval Empire.” P. 172.

[3] Ibid. P. 58.

[4] Bosl, Die Reichsministerialität Der Salier Und Staufer: Ein Beitrag Zur Geschichte Des Hochmittelalterlichen Deutschen Volkes, Staates Und Reiches. P. 63.

[5] Ibid. P. 39.

[6] Ibid. P. 40.

[7] Bosl, Die Reichsministerialität Der Salier Und Staufer: Ein Beitrag Zur Geschichte Des Hochmittelalterlichen Deutschen Volkes, Staates Und Reiches. P. 41.

[8] Ibid. P. 41.

[9] Arnold, “German Bishops and Their Military Retinues in the Medieval Empire.” P. 171.

[10] Bosl, Die Reichsministerialität Der Salier Und Staufer: Ein Beitrag Zur Geschichte Des Hochmittelalterlichen Deutschen Volkes, Staates Und Reiches. P. 41.

[11] Ibid. P. 42.

[12] Ibid. P. 45.

[13] Arnold, “German Bishops and Their Military Retinues in the Medieval Empire.” P. 171.

[14] Bosl, Die Reichsministerialität Der Salier Und Staufer: Ein Beitrag Zur Geschichte Des Hochmittelalterlichen Deutschen Volkes, Staates Und Reiches. P. 42.

[15] Hechberger, Adel, Ministerialität und Rittertum im Mittelalter. P. 3.

[16] Bosl, Die Reichsministerialität Der Salier Und Staufer: Ein Beitrag Zur Geschichte Des Hochmittelalterlichen Deutschen Volkes, Staates Und Reiches. P. 74.

[17] Bosl, Die Reichsministerialität Der Salier Und Staufer: Ein Beitrag Zur Geschichte Des Hochmittelalterlichen Deutschen Volkes, Staates Und Reiches. P. 86.

[18] Ibid. Pp. 87-88.

[19] Ibid. P. 95.

[20] John B. Freed, Noble Bondsmen: Ministerial Marriages in the Archdiocese of Salzburg, 1100-1343 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2019), https://doi.org/10.7591/9781501734670. P. 65.

[21] Judith Hurwich, “Marriage Strategy among the German Nobility, 1400-1699,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 29, no. 2 (1998): 169–95. P. 194.

[22] Ibid. P. 174.

[23] Burkard Keilmann, “Landolf von Hoheneck,” in Die Bischöfe des Heiligen Römischen Reiches 1198 bis 1448: Ein biographisches Lexikon, ed. Erwin Gatz (Berlin: Duncker und Humblot GmbH, 2001). P. 863.