What is Beauty?

Is beauty intellectual, emotional, or experiential? Or perhaps none of the above?

We are often told that "beauty is in the eye of the beholder” when confronted with an object whose beauty is open to interpretation. Why are we told this? Is it because beauty is intellectually subjective, or because designating something as ugly may insult the creator of the object, or because beauty is experiential and thus different to all? Some may say “all of the above”.

If all of the above responses applied —that beauty is subjective, personal, and experiential—then would it not mean that other aspects of our reality fall within a similar categorization? Religion is typically discussed in similar terms, making it difficult to reach a consensus. However, if it were true that beauty is highly personal, then why do so many people share an intrinsic understanding that some things are more beautiful than other things?

The Paris Opera House

Years ago, I was vacationing in Paris with my parents and siblings when we visited the Paris opera house, L’Opéra Garnier. As one of the more remarkable 19th century buildings in Paris, we opted for a guided tour led by a member of the theatrical corps, who provided us an in-depth and historical account of the building and its various functions.

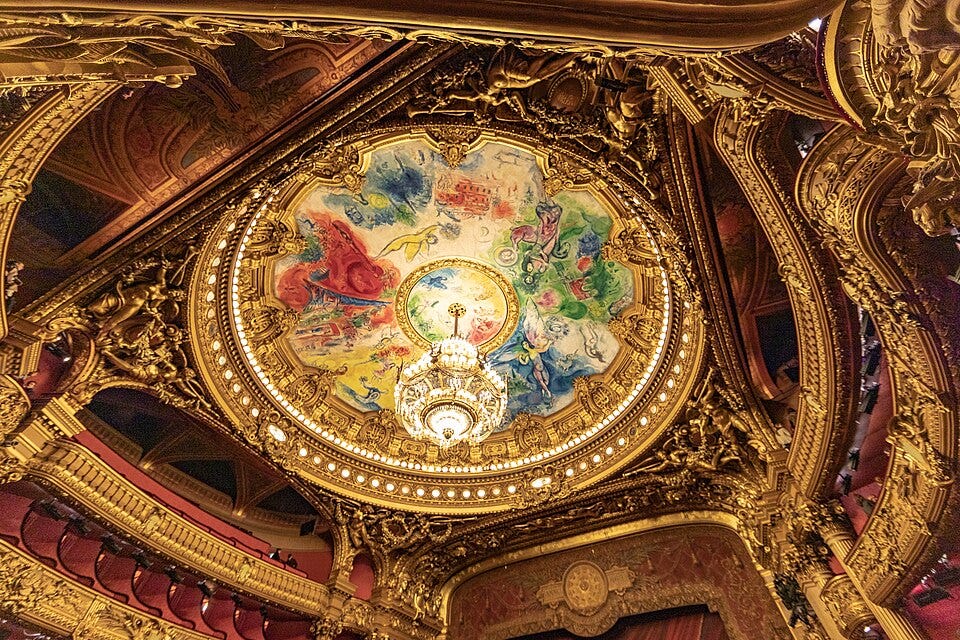

Given that it is a 19th century building, and that we are chiefly concerned with older things on this Substack, we will not dwell on the architecture but rather upon one element: the painted ceiling of the auditorium by the 20th century modern artist, Marc Chagall.

Chagall is revered as one of the greatest modern artists, and indeed the title is well deserved under the consideration that he is never compared with artists from other periods, such as Monet. For those unfamiliar with his work, he was fascinated with colors and produced many stained glass works that either replaced glass that had been destroyed—like in St. Stephan in Mainz, Germany—or works no longer tolerated by those entrusted with cultural heritage monuments—such as St. Etienne in Metz, France.

Chagall also produced many paintings, again with the emphasis of color rather than form. That is not to say that form is absent—that figures and symbols are entirely lacking, as they certainly are not. However, the figures are true representations of the modern-art movement of the 20th century in that they are quite abstract. Human forms are deconstructed with eyes vertically placed atop one another and hoble about with asymmetrical arms—sometimes bordering on mimicry of Picasso’s work.

In any event, the ceiling of the gilded auditorium features a vibrantly colored work by Chagall, though the rest of the interior is a mixture of classicist and baroque elements. One might venture so far as to say that Chagall’s work feels out of place. The seriousness of the theatre is not only challenged by the lofty, unrefined figures floating about, but entirely dismissed by their mere presence. It is as though theatre is simply theatre, a thing whose importance as an art form so revered in the century prior is now subservient to the blurred colors of Chagall’s fantasy.

When asked by the tour guide whether or not we enjoyed Chagall’s vibrant ceiling featuring swirls, spirals, and even what appears to be a grotesque man upon a unicycle, the responses from our group were mixed. Interestingly, they were separated by generation: those older than 50 seemed to enjoy the lightness that it offered, whereas those under 50 seemed somewhat annoyed by its presence, paired with the feeling that it was robbing the theatre of its intrinsic beauty and grandeur.

Nevertheless, everyone simply understood that was the way things were, until the tour guide showed us the original ceiling by the Classicist artist Jules-Eugène Lenepveu. Without wading too deep into the differences of the two works, we will simply refer to the images of both and leave it to your own discretion.

What Happened to Beauty?

Both Lenepveu’s ceiling and Chagall’s ceiling are regarded as masterpieces, though the artistry of both are not of the same caliber. The use of color is more refined by Lenepveu, as is his attention to form and overall design. Chagall, on the other hand, uses blurred lines, vibrant colors that lack variations in hue, and brutish winged figures that are recognizable as angels, but only just so.

Whereas Lenepveu captured the gravity of the 19th century theatre, Chagall introduced levity. However, all things have their place and not everything can or ought to be inverted. Within this small example lies the heart of the argument for beauty: namely that our common understanding has shifted from self-evident to self-justifying.

Since the early 16th century, Western society has consistently followed along a path of self-justifcation that, more often than not, takes the form of trimming away anything that interferes with self-expression. Tradition and history are viewed as vestiges of a past world whose relevance is disregarded by the mere fact that time has moved on—an ironic notion considering that both tradition and history become richer with the passing of time.

This pruning occurs under the guise that the more one removes, the closer to purity one comes. However, this purification is not the silver seven-times refined as found in Psalm 12, as refining silver is time-intensive and asserts that the silver (something pure) was always present. Our modern world does not concern itself with things that take time, as such things are viewed as wasted time. Thus, to save time, the silver is simply removed in favor of the blemishes.

In this way, the silver that certainly was there, is no longer the immediate goal. Instead, the silver has become an abstraction—ones looks for the place that the silver might occupy while questioning the existence of the silver. This necessarily sparks a fascination in the rock and other materials that encased the silver, seeking beauty in places where none exists, yet persevering in the vain hope that it will become beautiful if only one has the proper mindset. Thus, the search for beauty finds itself among the portion of the ore that turns to ash and not the portion that can always be refined.

Beauty will always Persist

We try to remain optimistic on this Substack—a notion supported by recent efforts to create new areas that embody older architectural designs (see the reconstruction of Le Plessis-Robinson near Paris). Previous generations that were raised with the idea that tradition and history are unnecessary in favor of undefined progress are now challenged by younger generations seeking a return to the past.

Visitors to Belgium, for example, are more willing to visit the late gothic cities of Ghent or Bruges rather than the post-modern Louvain-la-Neuve. The Louvre in Paris attracts more visitors and fascination than the Centre Pompidou just down the street. In terms of public interest, Da Vinci’s Mona Lisa prevails over anything by the modernist Paul Klee.

This is not to say that modern and contemporary art and architecture ought to be entirely dismissed, but instead viewed as an interregnum of the regency of beauty. Certainly beauty exists in Chagall’s stained glass when the light shines through in breath-taking tones. Picasso’s Guernica captures the chaos and horrors of war that few other paintings can boast. However, these are largely outliers due to the mastery of the artist rather than the beauty of the style.

Beauty has always mattered and is universally understood as an essential component of design across time, region, and culture. As something intrinsic, any attempt to “explain it away” or to convince someone that something is beautiful when it is not, serves only to undermine the nature of beauty. It certainly is in the eye of the beholder, but it is not dependent upon the beholder’s intellect, emotions, or experience.