Who were the Lombards?

The Lombards were notorious for war campaigns and antagonism toward their neighbors, but who were they really and where did they come from?

The cultural, legal, and architectural traditions of the Lombards did not cease after the Frankish Empire under Charlemagne conquered them in 774 AD. Instead, the identity they forged during the Early Middle Ages continued well into the 12th century, in which northern Italy united under the banner of the Lombard legacy, becoming a major player in the Holy Roman Empire.

The Germanic tribes destroyed Western Rome, right?

The concept of a vast migration of many warring tribes, overwhelming the Roman gates like a swarm of locusts is nothing more than a myth. What is true, is that certain groups of warriors served Rome as auxiliaries and then later as retainers of Roman provinces with the elevation of their kings to the status of the Roman foederati—as discussed in a previous article.

Another concept that regularly circulates classrooms like an unknown stench, is the concept that the Germanic tribes simply packed their families and livestock together in a feverish fury and migrated en masse to search for better living conditions for their people. However, the archaeological evidence from the origin of many of the Germanic groups in northern Germany and Scandia shows no sign of natural disasters having taken place, and furthermore, both the agricultural and cattle herding economies remained unchanged throughout the period of the 4th to 6th centuries.

Nevertheless, the myth of relentless waves of Germanic warriors and their savage families thrashing and burning the Roman world has persisted in the educational systems of Europe and America. Therefore, we will take a close look at the primary evidence in the form of the written and material record.

Where were they from and where did they go?

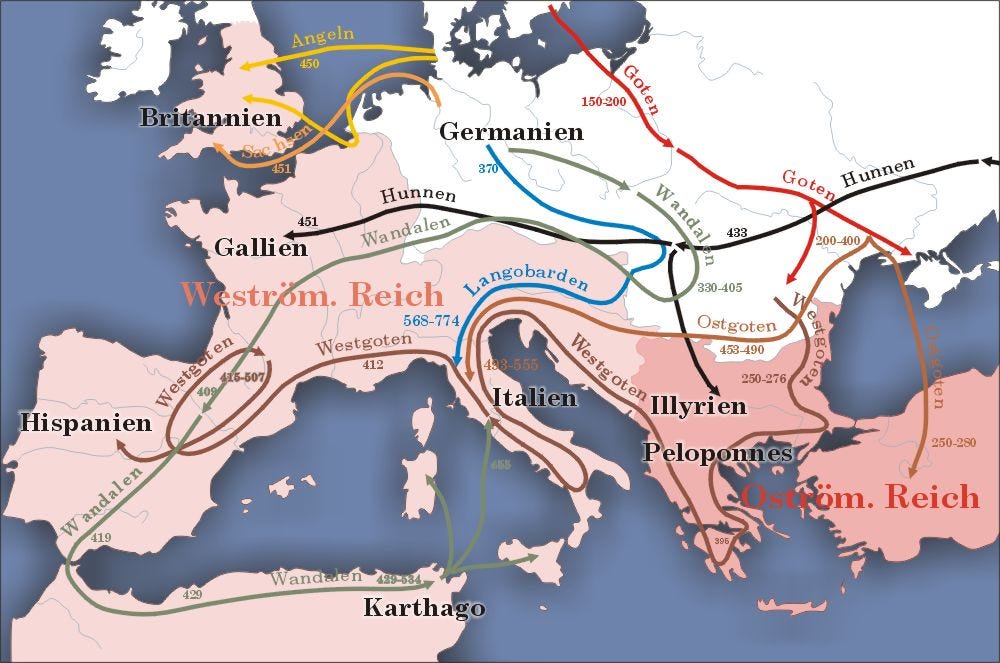

Like many of the Germanic tribes, the Lombards originated in northern Germany and Southern Scandinavia, known as Scandia. As presented in an earlier article about the collapse of the Western Roman Jurisdiction, the impetus for the Germanic tribes to venture into the Roman territory was a mix of opportunity in service of Rome as well as access to more resources and trade.

Their name is derived from a pagan story in which the Germanic god Odin (Wotan, in German) and his wife, Frigga, were watching a battle ensue between the Vandal and the Winiler tribes. Odin favored the Vandals, whereas Frigga favored the Winiler, but the battle was just beginning and Odin was very tired. According to the Germanic myths, the side chosen by Odin would reign victorious, so he faced his couch towards the Vandals in expectation that he would choose them when he awoke.

However, after he had fallen asleep, Frigga mischievously turned his couch to face the Winiler instead, and informed them to send out their women into the battle, clad in armor with their hair over their breasts and cheeks to make them unrecognizable to her husband. When Odin awoke to see the progression of the battle, he could not identify the warriors that faced him, but was obligated to declare them the victors. Perplexed and upset that trickery was afoot he suddenly exclaimed, “What Longbeards are those!” and soon thereafter the Winiler won the battle. When translated into German, long is lang, and beard is Bart, from which the term Langobarden comes from and—after a series of transliterations and translations—the term Lombard.

Like most Germanic warrior bands, the Lombards mostly operated as large mercenary groups, sometimes serving the Romans, sometimes others, and most often serving their own designs. In contrast to the Franks, the Lombards were more Independent of Rome's political influence, leading their own campaigns against other Germanic and Hunnish groups—particularly the Gepids. Over time, their ranks lost many warriors, but also gained fellow travelers. In fact, archaeologists have identified a number of other cultural groups based upon the grave goods discovered in Lombard cemeteries, including the Heruls, Huns, Noricans, Pannonians, Saxons, and Suevi.

During the 530s AD, they were invited from the Upper Danube into Pannonia (Western Hungary and Eastern Austria), by Emperor Justinian I for their assistance in the Gothic wars, where they remained for only 40 years. In turn, Justinian assisted the Lombards in their war against the Gepids—indicating that Lombards were shrewd diplomats who clearly knew their own worth as a fierce, yet small warrior group.

While in Pannonia, they underwent many acculturations, incorporating various artifacts, or altering their own in order to assimilate with the dominant Roman culture. By the time the Lombards were prepared to enter Italy in 568 AD, they had amassed a force of 40,000-70,000, matching that of the Ostrogothic invasion of Italy one century prior. This large force would have been primarily warriors—many of whom joining from other groups—as well as a number of other people, including families and traders.

Admission to the group was very fluid—particularly in that phase of their history—but became more stratified once they settled in Italy. In fact, the closer one could trace their ancestry back to the Winiler or realted tribes, the greater privileges one would receive. Though in a time where written evidence was lacking and oral traditions reigned, it was quite simple to make claims without having to substantiate them. P. Geary, an American Medievalist, commented on the topic, stating:

Ethnicity was perceived and molded as a function of the circumstances which related most specifically to the paramount interest of a lordship. Thus a duke may have been Gallic when his birthplace was mentioned, but he was a Frank when talking of his close connection to the king, and an Alamannian when leading the Alsacian levy.

The large Lombard force entered Italy in 568 AD under the banner of King Alboin, a fierce warrior and belligerent pagan who cared very little about the Church, the clergy, or its buildings. His followers raided churches and pillaged their way until they had taken the Po Valley that lay vacant after the Byzantines removed the Ostrogoths.

The written record

Upon establishing themselves in Italy, the kings began to marry foreign princesses, such as the Bavarian Theudelinda (570 - 628 AD). She first married the Lombard King Authari, and helped usher in the official adoption of Catholic Christianity. Prior to the marriage, most Lombards followed either Germanic paganism or Arianism, a Christian heresy that claimed that Christ Jesus was subordinate to God and not co-eternal—causing no shortage of strife with their Catholic neighbors on all sides.

Theudelinda's second marriage was to a Thuringian duke, named Agilulf (590-616 A.D.), who had been elected as the new King of the Lombards. Thus, the Lombard King and Queen were not from Lombardic families, but that the ruling dynasties instead assumed a Lombardic culture that was slowly becoming more Roman.

The Lombard Kingdom also introduced a new code of laws under King Rothari (an actual Lombard), who had married Theudelinda’s daughter, Gundeberga. The code was entitled Edictum Rothari (Edict of Rothari) and applied only to Lombards, as a distinction was made between them and the Romans, who lived under the continuing Roman laws, though the distinction largely dissipated by the turn of the 8th century.

The edict was issued in November 643 AD at the Lombardic Gairethinx (assembly) and was similar to the Lex Salica (Salic Law) of the Franks, in that it contained many previously unwritten laws that were Germanic in origin. Though unlike the Lex Salica, the Lombardic Edictum Rothari was issued nearly 150 years later, illustrating a key difference between the Franks and Lombards—the Franks were quick to adopt the more advanced Roman culture, whereas the Lombards were far more stubborn.

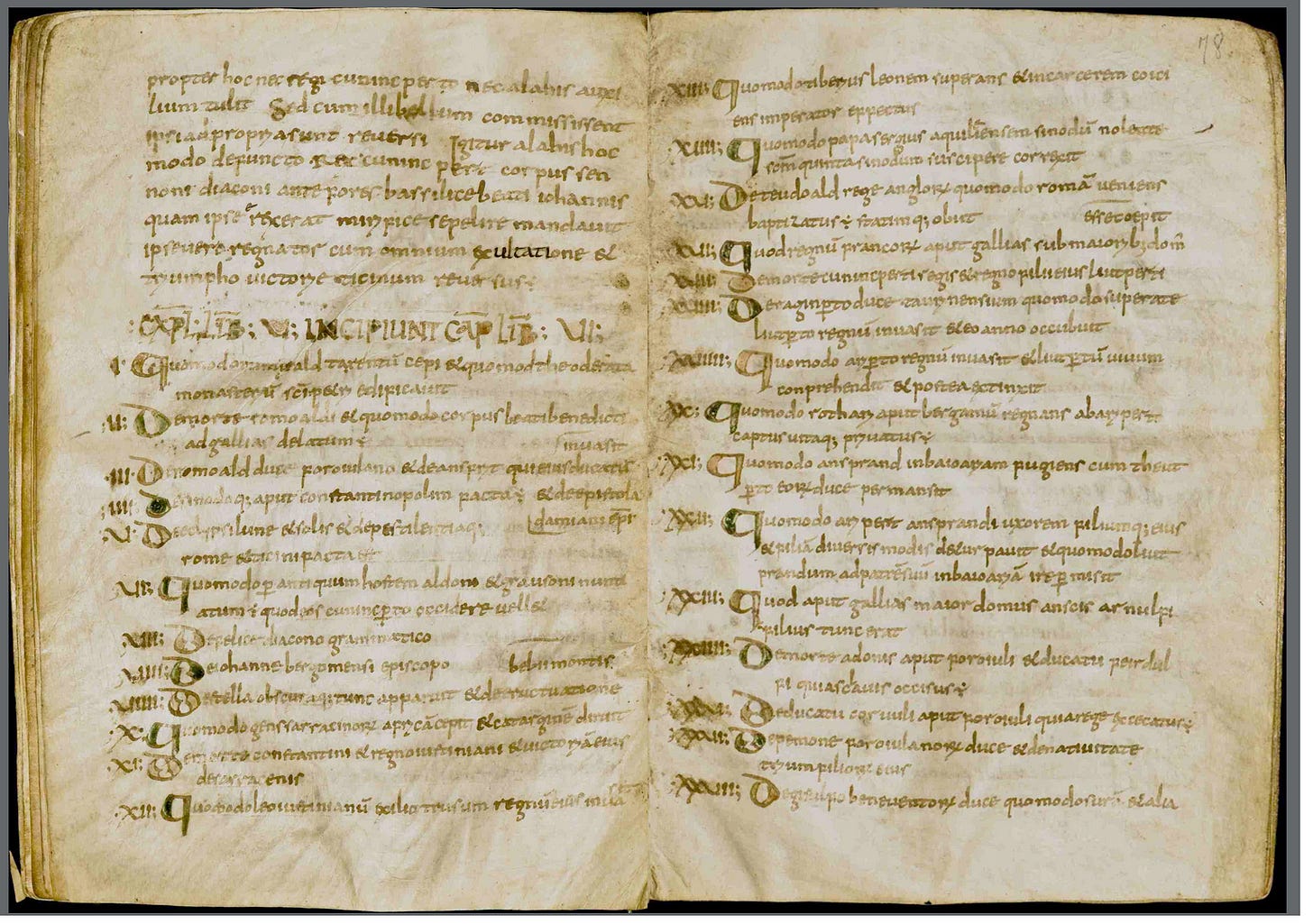

The most famous author of the Christian period of Lombard documentation was Paul the Deacon (~700 ~ 800 AD), a Lombard writer who composed the the six volume Historia Langobardorum (History of the Lombards). His text explored the culture and relations of the Lombards and even attempted to describe their ethno-genesis rather than reference the pagan myth. He focused upon events, kings and dukes, the integration of foreign tribes, and even the negotiations with the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I in the mid-6th century.

The manner in which his text approached the Lombards is very similar to the Liber Historiae Francorum (Book of the History of the Franks)—discussed in an earlier article—as both authors were writing about their own culture. It is noteworthy that Paul the Deacon composed his text after the Franks under Charlemagne had conquered the Lombard Kingdom. He nevertheless decided to end the chronicle with the death of King Luitprand in 743 AD, rather than the Frankish conquest of 774 AD.—a sort of literary farewell to the kingdom of his birth.

Social Status

According to the excavations of numerous Lombard cemeteries, an glimpse into the social structure can be gleaned. The various Lombard cemeteries along the path from Scandia to Northern Italy were typically in use for roughly 45 years, indicating the speed of the path to Italy.

During the Pannonian period, the warrior group composed 20-25% of the total buried population, though with two major groups among them: the freeman were found with short swords, lances, and shields; whereas the aldii (the semi-free) are found with bows and arrows. The cost of swords was substantially high well into the Middle Ages, as were lances.

This indicates that the Lombard warriors were by no means the majority of those being buried in the cemeteries, which in turn suggests simply fewer deaths, or that most warriors died on foreign battlefields, or that they were busy raising an army in peacetime. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that after their arrival in Italy, the warriors compose over 40% of the total burials.

The Necropolis at Dueville (just north of Viacenza, Italy) dates from the early 7th century to the early 9th century, and features skeletons situated from west to east in the manner of Reihengräber—meaning ‘Row Graves’, typical of Germanic burials, and exhibited in Frankish cemeteries of the same period. Interestingly, the cultural aspects that the Lombards and Franks shared most in common in the 7th century were their funerary practices and their treatment of those with Roman heritage.

While both the Franks and Lombards made Romans the sole taxpayers, the Lombards went one step further by depriving Romans of free status and forbade them from carrying swords.

The material record

The grave goods become more complex the more south that the Lombards traveled. Their fibulae (broaches that held overcoats and capes around one’s neck) were first based upon an animal-motif, and became ever more Roman over time, emphasizing the human form instead—zoomorphic to anthropomorphic. They are ever more inlaid with human portraits, surrounded by human heads protruding from the top.

These portraits provide insight to the culture in which the hair was always cut to the level of the ears, and the moustaches and beards were neatly kept. However, after their conversion to Catholicism, a preference emerged for the faces to depict Christ, rather than a generic Lombard.

Besides the fibulae, gold wares and swords also became increasingly more intricate as the Lombards moved south, indicating more trade connections with Eastern Rome, and generally more access to resources.

The pottery from the Danubian area (one of their first ‘stops’) was not continued by the Lombards after they entered Pannonia, though they did continue the stamping decoration found along the Danube and the European North. Instead, the Lombards brought a Pannonian-style pottery with them into northern Italy—indicating that they had adopted more cultural items than when they were along the upper Danube. Further hybridization of their pottery occurred once the Lombards entered Italy, in which the Pannonian styles were finished with Roman glazes (typically brown or green).

While in Pannonia, the Lombards settled in the former Roman towns, which were by no means abandoned. The freemen and servants assimilated with the common folk of Pannonia, though the kings and dukes remained slightly separate, marrying into Bavarian or Thuringian Dynasties.

Summary

The Lombards continuously adopted new technologies and even combined their language with Latin once they arrived in the Po Valley (of which there are 300 remnant words in Italian). The evidence clearly demonstrates that as Germanic groups came more in contact with the Christianized Roman culture of the 7th and 8th centuries, they shed many of their destructive practices, such as raiding and the slave trade, and adopted the the Roman culture.

The Lombards represent perhaps the most fascinating case of a people who transitioned from arguably the closest example of the stereotypical barbarian, to a people that would go on to revolutionize sacred architecture. Their efforts to promote the Roman architects networks on the banks of Lake Como ushered in what is known as the pre-Romanesque period of the late 8th to early 11th centuries.

A future article will explore this incredible period in more detail, comparing the Frankish Merovingian and Carolingian architecture with the Lombardic architecture. The fusion of these styles gave rise to the imperial cathedrals along the Rhine constructed by the Holy Roman Emperors, who demonstrated their inherent connection to Rome through its architectural legacy preserved by the Lombards.

The sources for this article can be found here!

Carrara, Nicola. “The Lombard Necropolis of Dueville (Northeast Italy, 7th-9th c. AD): Burial Rituals, Paleodemography, Anthropometry and Paleopathology” 9, no. 2 (2013): 259–71.

Christie, Neil. “‘Byzantines, Goths and Lombards in Italy: Jewellery, Dress and Cultural Interactions.’” In 'Intelligible Beauty’. Recent Research on Byzantine Jewellery, edited by C. Entwistle and N. Adams, 9. London: British Museum Press, 2010. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304490724_'Byzantines_Goths_and_Lombards_in_Italy_jewellery_dress_and_cultural_interactions'.

Guerber, H.A. Myths of the Norsemen. New York: The Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading, 2006.

Harrison, Dick. “Dark Age Migrations and Subjective Ethnicity: The Example of the Lombards.” Scandia: Tidskrift För Historisk Forskning 57, no. 1 (1991): 18.

Heather, Peter. Empires and Barbarians: The Fall of Rome and the Birth of Europe. 1st ed. New York City: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Kiszely, István. The Anthropology of the Lombards. Translated by Catherine Simán. Vol. 1 and 2. International Archaeological Reports since 1974. Oxford: B.A.R. Publishing, 1979.

La Salvia, Vasco. Archaeometallurgy of Lombard Swords from Artifacts to a History of Craftsmanship. Università Degli Studi Di Siena 43. Florence: All’Insegna del Giglio, 1998.

Musset, Lucien. The Germanic Invasions - the Making of Europe. Translated by Edward James. New York, NY: Barnes and Noble, Inc., 1993.

Paul the Deacon. History of the Lombards. Edited by William Dudley Foulke. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1974.