Knightly Poets, Part I: An Introduction

This is a new series dedicated to the German Minnesänger of the Holy Roman Empire who dominated the court culture at the turn of the 13th century with their poems and songs that continue to inspire.

As this is the first part of this series, we will begin our journey by exploring the world of chivalry, the ideal that knights sought to attain, and the key source materials to support our study.

Courtly Chivalry

The medieval court had many manifestations throughout Europe. However, courtly life was not restricted to life at the court. The introduction of chivalry during the High Middle Ages completely transformed society by fixing its gaze upon an ideal warrior who foremost protected the innocent, served others, and dedicated himself to God.

Many went beyond their existential duties and explored the arts and literature, becoming warrior poets who dueled not only with sword and spear, but also in song and verse. As this Substack is devoted to the Holy Roman Empire (HRE), we will discover the lives of the German Minnesänger (minstrels) who took the courtly life of the 12th and 13th century by storm.

But first, we must define who it was precisely that engaged in the composition of poetry and song and their role in the courts of the HRE. As has already been mentioned, knights were heavily involved in the culture of the Minnesang, but it was not exclusive to them. Nevertheless, they composed the bulk of the most famous Minnesänger and there was a very good reason as to why.

What did a Knight’s Training Emphasize?

The topic of the virtuous noble, the development of the nobility, and the determinations of noble status have been explored in a previous article entitled: Where did the Nobles come from? As such, we need not recount what has already been said, except that the concept of being noble was inextricably bound to an expectation of virtuous behavior.

The culture of chivalry was in essence an incubator for raising young men to become learned warriors whose behavior, mannerisms, and etiquette were closely studied by all. This provided a constant feedback loop that either praised or corrected these young men on their path to knighthood.

Those fortunate enough to receive their training from imperial knights—either nobles or ministeriales—were privy to the elite courts of the empire. These courts provided a physical location where young squires and knights could network with one another and hope to one day take the hand of a noble lady.

However, the ladies at court were themselves daughters or wives of knights, who had high expectations in the world of chivalry, seeking a suitor for themselves or for their daughters who excelled in virtuous behavior. Thus, chivalrous behavior was indicative of a pursuit of virtue, or put more plainly, chivalry was less of a goal, as it was a means.

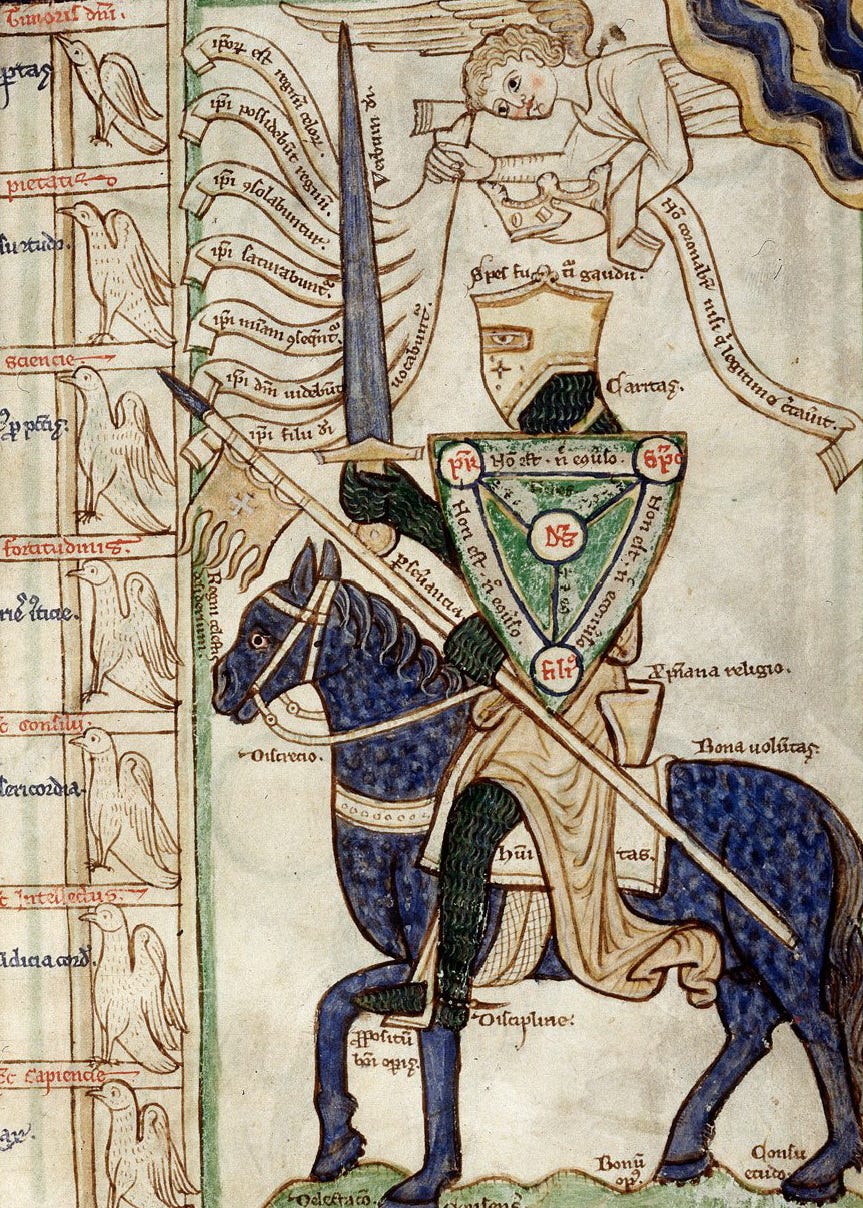

The chivalrous pursuit of virtue set the ideal toward which knights were to orientate themselves—an ideal that was coupled with an intense faith and admiration of those individuals who had excelled both in virtue and faith. These noteworthy people were the saints, whose queen is the Mother of God—whom the knights believed was the embodiment of perfect virtue and sublime faith, and therefore the guide upon that journey.

It must be underlined that we are speaking of an ideal, a goal toward which a person struggles their entire life though never fully attains it. One can excel in virtue and faith, like the saints have, but one can never fully embody both. This shortcoming can either be aggravated through pride or mitigated through humility, bringing up a key aspect of chivalry—the denial of self. Besides treading the battlefield as fearsome warriors or owning feudal lands, knights were servants. Their service was toward their liege lords, their family, and God (in ascending order).

Their duties in that service were to protect all three by mastering the balance between meekness and martiality. Meekness embodies patience, obedience, and a fond attention for subtleties—most notable in the proper treatment of women. In contrast, martiality expresses the ability to instill fear through force of arms or wit as it pertains to strategies and tactics. Meekness and martiality represent a balancing act that must be practiced every day and directed toward the appropriate recipient. An excess in one results in the deficiency of the other and thus a departure from the mean.

Medieval knights were trained in the martial arts of warfare, learned courtly etiquette, practiced humble service, and dedicated free time to the arts. Those at an imperial court were also well versed in song, poetry, literature, and philosophy during the tenure of their training. However, whether a knight continued in that manner upon ending his training was entirely up to him.

To that end, knights had an array of soldierly examples to follow: St. Michael the Archangel for war, St. Martin of Tours for humble service, St. Maurice of the Theban Legion for remaining true to their faith—among many others. Beside the saintly role models, there were of course their trainers, fathers, uncles, brothers, and priests who prepared them for both the court and the battlefield.

A knight was therefore a member of a greater community following a tradition that drew inspiration from centuries of heroes who excelled in the faith-guided chivalrous pursuit of virtue. To be separated from that community either spiritually or physically indicated a divergence from that pursuit in its proper form.

Modern Rejections of Chivalry

The common naysayer channeling the reflexive objections to tradition embraced by the ‘enlightenment’ may claim: “What about the 11th century knights who sacked and massacred the Jewish district of Worms on the eve of the first crusade? Or the 14th century robber knights who terrorized the hinterland of the Electorate of the Rhine? They were knights and lived in a chivalric world. Were they not also products of that same culture and thus indicative of a societal rot caused by that culture?”

To which a question can be posed in response: “Did these ‘knights’ demonstrate the pursuit of virtue in their actions, or an obedience to the Church that anathematized such behavior, or a proper balance of meekness and martiality?” The answer is, of course, a resounding ‘no.’ It is also worth mentioning that the murderers of the Jews prior to the first crusade were themselves destroyed by knights serving the Archbishop of Mainz, whose successors also uprooted the robber knights three centuries later.

Evildoers who happened to have been trained as knights, yet managed to forget their training and disregard chivalry certainly existed throughout the European Middle Ages. However, they were the exceptions, not the norm. As such, their behaviors are indicative of poor judgement, a lack of prudence, an excess of fortitude, and a disregard for temperance—violators of the four cardinal virtues.

Nevertheless, modern media—especially cinema—has continued the ‘enlightened’ quest to not only uncouple the guiding light of faith from that chivalrous pursuit, but also to cleave knightly action from chivalry itself. The result is a hollow shell of a knight who follows an unformed conscience according to his own will in the pursuit of self-preservation.

Perhaps the most perverse iteration of this falsehood is the popular Game of Thrones series, in which knights are knights in name only, eager to follow desire and succumb to their lower passions. This is the antithesis of a knight, yet has woefully provided the image of a knight for the ignorant masses.

Making Amends for False Interpretations

The effort to remedy such confounded misinterpretations that permeate even medieval studies programs must be undertaken with a strict attention to the source material. These sources include chronicles covering all topics of the medieval world. It ought to be underlined that medieval chroniclers were as keen to highlight offenders to the chivalric pursuit, as they were to praise those who excelled in it.

Provided that most chroniclers were clergymen, they were raised in the same courts as the knights and often had family members who were knights. Among their ranks are counted Arnold von Lübeck, Ekkehard von Aura, Gerald of Wales, Rahewin, William Perault, and many others. As both insiders and outsiders to the knightly realm, they were the ideal specimen to qualify a knight’s grasp of virtue—or lack thereof.

However, chroniclers were not the only ones to write about courtly life, because the knights themselves did so as well! We will now reintroduce the Minnesänger mentioned at the beginning of this article as the purveyors of that court culture who lived it and recorded their experiences.

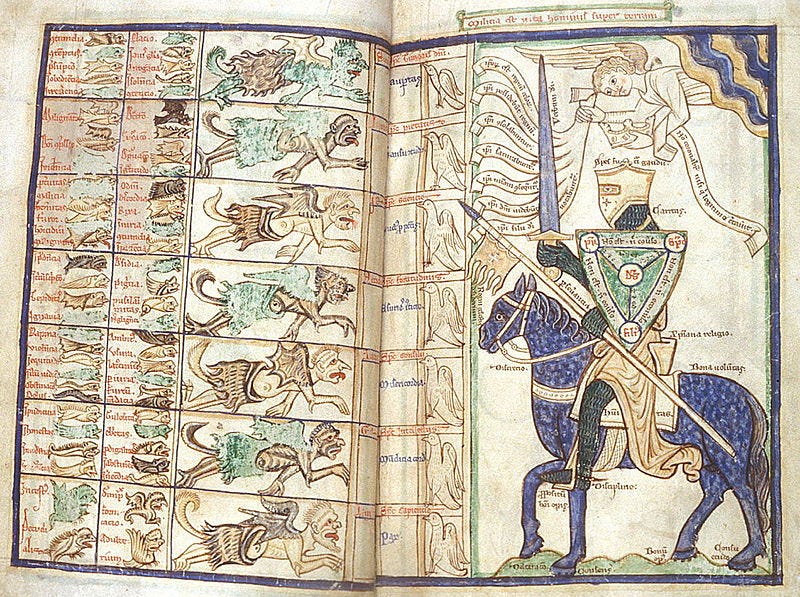

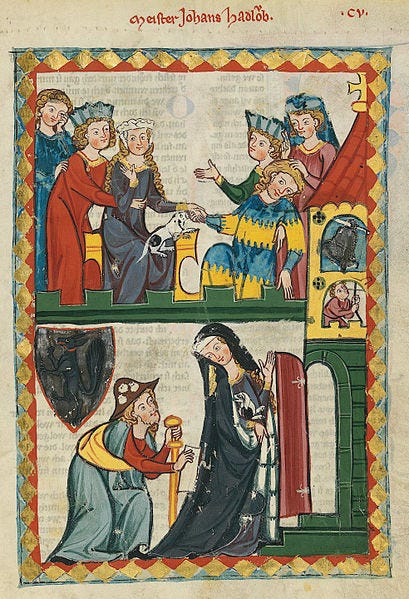

The Codex Manesse

Fortunately, the compositions of the Minnesänger have been well-preserved throughout the ages—a testimony to their cultural value over time. Some of the most famous poems are located in the Codex Palatinus germanicus 848, also known as the Codex Manesse, that includes 140 medieval texts on 426 pages of parchment. The compilation was completed in the early 14th century by Johannes Hadlaub, a Minnesänger from Zürich, who received an assemblage of romantic poems that had been collected by a prominent burgher named Rüdiger Manesse the Elder.

The knightly Manesse family had been collecting poems and songs about love, which had been composed by the Minnesänger of the late 12th to late 13th centuries. Hadlaub led a group of collectors and interested parties who served as editors of the new collection. These editors included abbots, abbesses, bishops, and knights who worked together to produce the codex.

Although it was produced in Zürich, it was transferred through many hands before landing in Heidelberg—the capital of the Electorate of the Rhine—in 1604 AD. It was soon placed in the illustrious Biblioteca Palatina that housed thousands of books and manuscripts making it one of the largest libraries in Europe during the 17th century.

In a previous article, we explored the daft decisions of the Winter King, Frederick V, who lost the Electorate of the Rhine to his cousin, Maximilian I of Bavaria. During the Thirty Years War, Maximilian took the Biblioteca Palatina as a prize following the dismissal of his cousin and offered the entire library to the Vatican—where the collection still resides.

However, the Winter Queen, Elizabeth Stuart, managed to steal away the Codex Manesse before Maximilian’s conquest and gave it to a friend for safe keeping, who later sold his private collection to the King of France. The Codex Manesse traveled to Paris as a hostage to the sale where it remained in obscurity in the royal library until a certain folklorist discovered it: Jacob Grimm.

Upon its rediscovery, the codex became the object of a campaign to return the key texts of German literary heritage back to German lands. Multiple parties got involved, but given the sheer age and value of the codex, the only way to repatriate it would be to exchange it with something of similar value—which happened to be an entire library of French texts that had been in Strassbourg.

Ultimately, the quest succeeded in the late 1880s with a direct involvement from the imperial German government who provided 400,000 golden marks for the disposition of the codex. Since that time, the codex has been in Heidelberg where it is often on display and provides one of the greatest sources of study for researchers in the humanities. In fact, the entire text, including high-resolution scans of each page is available here: https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/cpg848?&ui_lang=eng.

Other Compilations

A number of other compilations exist as well, each bearing a strong connection and even an overlap with the Codex Manesse. They include:

The 13th century Codex Buranus, or Carmina Burana, with 254 texts.1

The early 14th century Naglersche Fragment: two parchments that were possibly produced as a prototype of the Codex Manesse.2

The late 13th century Codex Germanicus 92, or Budapester Liederhandschrift: three parchments recently discovered in the 1980s.

The early 14th century Weingartner Liederhandschrift: 170 parchment pages, often referred to the ‘little sister’ of the Codex Manesse.3

The mid-13th century Codex Palatinus germanicus 357, or Kleine Heidelberger Liederhandschrift: 45 parchment pages and oldest of the major compilations

These five additional sources will provide more material for this series as their combination generates a more complete view of the various poets that will be explored. The larger codices are available online whereas the fragments are slightly more difficult to research. Nevertheless, a fair amount of research has been conducted on all of them, thus providing an excellent foundation for their use.

Summary

Two notions of particular importance stand out:

First, chivalry is less of a goal in of itself, as it the means toward perfecting one’s life in accordance with virtue, which in turn is made known through faith. This faith was cultivated by the Church, who identified the greatest among its flock as representatives of that ideal: the saints. To separate the Christian faith from a proper sense of chivalry would be to neglect the importance of the former, and thoroughly disintegrate the latter.

Second, most of the source material in support of this claim is freely, readily, and digitally available to research and interpret. The Codex Manesse provides the greatest understanding of chivalry through the eyes of those who lived it. The other medieval chronicles—which are too many to list in this article—provide context as to how knights were seen by others.

Going forward in this series, we will use the various codices of poems and medieval chronicles to evaluate chivalry within its context and interpret the writings of the Minnesänger.

For more reading, check out these sources:

Bauschke-Hartung, Ricarda. „Burgen und ihr metaphorischer Spielraum in der höfischen Lyrik des 12. und 13. Jahrhunderts“. In Die Burg im Minnesang und als Allegorie im deutschen Mittelalter, 11–40. Kultur, Wissenschaft, Literatur 10. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang GmbH, 2006.

Hansen, Walter, Hrsg. Die Minnesänger. Die Liebespoesie des Mittelalters. Rheinbach: Regionalia Verlag GmbH, 2015.

Jones, Robert. Knight - the Warrior and World of Chivalry. Oxford: Osprey Publishing Ltd., 2011.

Lieb, Ludger, und Jacob Klingner. „Flucht aus der Burg“. In Die Burg im Minnesang und als Allegorie im deutschen Mittelalter, herausgegeben von Ricarda Bauschke-Hartung, 139–60. Kultur, Wissenschaft, Literatur 10. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang GmbH, 2006.

Voetz, Lothar. Der Codex Manesse: Die berühmteste Liederhandschrift des Mittelalters. 1. Aufl. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 2015.

Zoozmann, Richard, Hrsg. Der deutsche Minnesang: Liebeslieder des Mittelalters. Cologne: Anaconda Verlag GmbH, 2011.

https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb00085130?page=,1

https://archive.org/details/jbc.bj.uj.edu.pl.NDIGORP006047/page/6/mode/2up

https://digital.wlb-stuttgart.de/sammlungen/sammlungsliste/werksansicht?tx_dlf%5Bid%5D=12064&tx_dlf%5Border%5D=title&tx_dlf%5Bpage%5D=5&cHash=8b6958267880e882c51462458a7a199d